When you hit your 40s, it’s only natural to want to try new things.

That little platitude holds true not only for those suffering midlife crises, but also, apparently, for at least one spacecraft launched by NASA. Just a few months after celebrating its 41st birthday, the Voyager 2 probe has left its familiar environs and entered interstellar space — only the second human-made object in history to do so, after Voyager 1 did it in 2012.

“I think we’re all happy and relieved that the Voyager probes have both operated long enough to make it past this milestone,” Suzanne Dodd, the Voyager project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement released Monday. “This is what we’ve all been waiting for.”

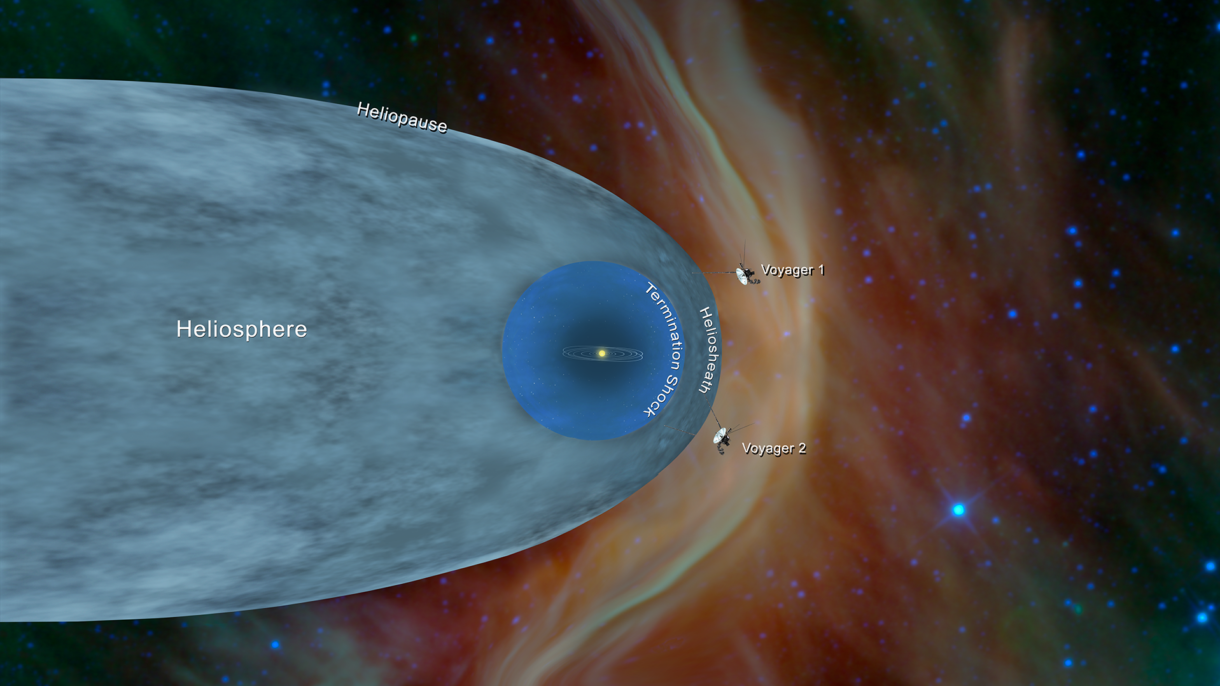

The moment they were waiting for arrived early last month, when Voyager 2 left what’s known as the heliosphere — the vast bubble of plasma and particles generated by the sun and stirred in solar winds. This bubble ends at a boundary called the heliopause, where the sun’s magnetic field peters out and solar winds give way to interstellar space.

“Inside the bubble, most of the material has come from our sun and the magnetic field has come from our sun,” Voyager project scientist Ed Stone explained in a video provided by NASA. “Outside the bubble, most of the material comes from other stars that exploded 5, 10, 15 million years ago.”

NASA concluded the probe had crossed the heliopause when a key instrument on board “observed a steep decline in the speed of the solar wind particles on Nov. 5,” the JPL said. “Since that date, the plasma instrument has observed no solar wind flow in the environment around Voyager 2, which makes mission scientists confident the probe has left the heliosphere.”

By one definition, that also means Voyager 2 — now more than 11 billion miles from the sun — has achieved another, much simpler-to-say feat: leaving the solar system.

It’s not the only definition, though. And the JPL itself marks the end of the solar system at the edge of the sun’s gravitational influence, on the outer boundaries of the Oort Cloud. By that measure, the lab explained, both Voyager probes “have not yet left the solar system, and won’t be leaving anytime soon.”

“It will take about 300 years for Voyager 2 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud,” it said, “and possibly 30,000 years to fly beyond it.”

Of course, that’s a rather long time — particularly when one considers that the Voyager probes are already massive overachievers when it comes to longevity.

Launched 16 days apart in 1977, the two spacecraft completed their original mission — observing Jupiter and Saturn — in the early 1980s before turning their focus to Uranus, Neptune and beyond. It was nearly two decades ago that Voyager 2 made its fly-by past Neptune, the outermost planet of the solar system (since Pluto’s tragic demotion, at least).

“It’s really two generations ago” that the probes launched, Dodd said.

“You can think of what the technology was. Your smartphone has 200,000 times more memory than what the Voyager spacecraft have,” she added. “So it’s just exciting that we’ve been able to get it into interstellar space.”

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))